How Dennis Peron and LGBTQ Activists Overcame Police Violence and the AIDS Epidemic to Win the Battle for Medical Cannabis

Dennis Peron may not have the same fame as weed icons like Bob Marley, Willie Nelson, or Snoop Dogg—but he absolutely should. Every single time we raise a legal joint, bong, rig, vape pen, or edible to our lips, we should genuflect to honor the late Peron’s memory.

He’s hailed as a father of medical marijuana, but Peron’s movement struck a major blow against all cannabis prohibition. The legal framework he and his allies designed for medical cannabis in California paved the way for other states to legalize, normalized the concept of cannabis as medicine nationwide, and demonstrated to the rest of the country that granting citizens legal access to the plant would not, in fact, result in chaos, mass addiction, or the destruction of society. Pride Month is a great time to remember that every single person currently enjoying legal cannabis owes a huge debt to Dennis Peron, HIV/AIDS activists, and the LGBTQ community. This grassroots social movement overcame anti-gay bigotry, police violence, and a devastating epidemic to win the long, arduous fight for patients to use cannabis as medicine.

A Vietnam Veteran Starts A Cannabis Collective

Though he is forever associated with San Francisco, Peron was born in The Bronx in 1945. His first deep dive into cannabis came during his tour of duty in Vietnam. In the 2012 book Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana, Martin A. Lee quotes Peron as saying “Saigon was filled with the sweet smell of marijuana,” and says that smoking cannabis was one of the ways Peron endured the horrors of the war. After he was discharged in 1969, he brought two pounds of Thai weed with him to San Francisco, where he set up a pot collective in the Castro.

Over the next two decades, Peron pioneered cannabis businesses and activism. In 1974 he opened a health food restaurant he named the Island (after Aldous Huxley’s novel about a psychedelic utopia). The Island sold vegetarian food and gave complimentary joints to all patrons; upstairs was a collective called the Big Top, where patrons could buy all kinds of cannabis. “About 200 to 300 people a day came,” Peron says in Smoke Signals. “I treated them with respect and gave them their money’s worth. It was like a dream. People loved it.” Right from the start, Peron’s risky personal activism was always paired with grassroots movement-building: Anyone who purchased pot on the premises of the Island was required to register to vote.

The Island became a central hub for the burgeoning Bay Area gay rights movement (Harvey Milk, a friend of Peron’s and later the first-ever openly gay elected official in California history, used the restaurant as his campaign headquarters). From the beginning, LGBTQ organizing and political influence went hand-in-hand with the movement to reform marijuana laws. Milk in fact launched his political career going door-to-door in the Castro with petitions for the California Marijuana Initiative in 1972.

San Francisco in the 1970s may have been a gay mecca, but it was not a safe space. Until 1974, the American Psychiatric Association still categorized homosexuality as a pathology. Law enforcement in San Francisco was notorious for targeting gay and lesbian gathering places. Those arrested were often coerced into paying bribes to avoid being outed in the press. Police violence towards queer people was depressingly common. This was the cultural atmosphere in July 1977, when a San Francisco narcotics squad raided Peron’s restaurant.

Though he was unarmed, a cop named Paul Mackavekias shot Peron in the leg, shattering his femur bone. He and 13 others were arrested. During Peron’s trial, Mackavekias shouted in a moment of anger that he wished he’d killed Peron so there’d be “one less faggot in San Francisco.” All of Mackavekias’s testimony was thrown out as a result, resulting in a more lenient sentence for the defendant. Peron spent six months in San Bruno County Jail, where he somehow remained amazingly optimistic, writing to High Times magazine “Watch the light from San Francisco; it will light up the world.”

Peron used his time in prison to draft and launch a campaign for Proposition W, a San Francisco citywide ballot measure that directed police to stop arresting or prosecuting people for cannabis. Proposition W won easily, and then-mayor George Moscone notified the San Francisco police that they should bow to the will of the people and ignore minor marijuana infractions. Tragically, on November 27, 1978, Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk were shot and killed in San Francisco City Hall. Peron’s new cannabis decriminalization initiative died with them.

Their assassin, Dan White, was a homophobic ex-cop and disgruntled former member of the Board of Supervisors who became a folk hero to local police after the killings. (Not-so-fun fact: Dan White re-emerged in the 2021 news cycle when it was discovered that Fox News host Tucker Carlson listed himself as a member of the “Dan White Society” in his 1991 college yearbook.) Some officers wore shirts with the slogan “Free Dan White” under their uniforms. Law enforcement played “Danny Boy” in White’s honor on police radio and raised more than $100,000 for his defense. The assassination and police response to it further incensed LGBTQ civil rights activists, and when White was sentenced to just seven years in jail, tens of thousands of San Franciscans assembled at City Hall. In the ensuing violence, now known as the White Night riots, protestors broke windows, threw rocks and overturned police cars. Police beat and tear-gassed protestors, covering their badges so as not to be identified, eventually raiding the Castro in violent retaliation.

While the 1970s were fraught with conflict and risk for pot dealers and gay San Franciscans like Dennis Peron, the worst was yet to come.

How the AIDS Epidemic Galvanized Medical Cannabis Activism

HIV ravaged American gay communities, but few more than San Francisco’s. Between 1981 and 1986, 25,000 men in San Francisco died from Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. But as Tim Fitzsimons of NBC News pointed out, the AIDS epidemic “surged through communities that the straight world preferred not to see.” The terror and sense of emergency felt by gay Americans was ignored or minimized by political leaders and the mainstream media. A “gay disease” simply did not inspire action or empathy. When asked in 1982 whether President Ronald Reagan was tracking the spread of AIDS in 1982, Press Secretary Larry Speakes laughed. When Congress held its first hearing on AIDS in 1982, one reporter showed up. Reagan himself infamously did not mention AIDS in public until 1985.

In many ways, the horrors of the AIDS epidemic single handedly transformed medical marijuana access into an urgent human rights issue, because cannabis provided relief for many of the symptoms suffered by AIDS patients when there was literally no other treatment available. Cannabis proved an effective treatment for HIV-associated wasting syndrome, and eased the extreme pain of AIDS-related peripheral neuropathy. It also allowed patients to tolerate the severe nausea caused by the early HIV drug treatments of the late 1980s. People with HIV desperately needed cannabis, and no one did more to get cannabis to AIDS patients than Dennis Peron.

In 1990, Dennis Peron was living in the Castro with his partner Jonathan West, who was dying of HIV. Ten narcotics officers raided the apartment, showering the couple with physical abuse and homophobic taunts before arresting Peron for possession. Later, Peron said that a dream he had that night in jail inspired him to create the first-ever public medical marijuana dispensary. Though so sick he could barely walk, West testified at Peron’s trial that the cannabis police had found was his. The charges against Peron were thrown out, and West died two weeks later. Peron vowed to spend the rest of his life helping what he called “other Jonathans,” and founded the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers’ Club soon after.

The Making of Proposition 215

By its peak membership in 1995, the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers’ Club had 11,000 members, half of whom were people with HIV. The organization employed nearly a hundred people, and had become a gathering space where wheelchair-bound and chronically ill people could smoke safely and find community with others who understood their plight. On Tuesdays and Thursdays Peron gave away free bags of marijuana for poor patients, who now included people with cancer, glaucoma, arthritis, and multiple sclerosis as well as people with HIV.

Peron and his allies knew that they were breaking the law, and assumed they would be arrested (Peron had kept a defense lawyer on retainer for years at this point). Their work at the dispensary was about alleviating suffering—but it was also a practice of civil disobedience against unjust laws. Gay Americans had already seen what happened if they trusted law enforcement to respect their rights, or the government to recognize their plight. Not surprisingly, they took caring for the sick in their community into their own hands.

Dale Gieringer, who co-authored the medical marijuana initiative with Peron, says in the documentary Dennis: The Man who Legalized Cannabis that “It was Dennis’ idea first to do a medical marijuana initiative.” For years, Peron and his allies had discussed the possibility of a statewide ballot initiative for medical cannabis. Two bills legalizing marijuana for specific medical conditions had already passed in the California state legislature, but both bills were vetoed by Republican Governor Pete Wilson. Activists recognized that they needed to create a ballot measure that could not be quashed by a governor’s veto.

In addition to Peron, the organizers of this grassroots ballot measure campaign included California NORML, ACT UP, medical marijuana dispensary owners, labor organizers, doctors, lawyers, harm reduction activists, and hospice workers. The group spent months drafting and editing the text of the proposition, filing it in the state capitol on September 29, 1995. With just five months to gather nearly half a million signatures required to get the measure on the ballot, the organizers eventually got three quarters of a million. The measure was now on the ballot, and was formally named Proposition 215 .

Proposition 215 was vehemently and vocally opposed by powerful entities such as Clinton Drug Czar General Barry McCaffrey, California Attorney General Dan Lungren, the California Narcotics Officers’ Association (CNOA) and 57 of the state’s 58 district attorneys. Former presidents Carter and Ford spoke out against it, as did the then-senators of California Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer. Attorney General Lungren actually ordered a raid on the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers’ Club; on August 4, 1996, around 100 agents from the California Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement raided the club’s home at 1444 Market Street, cutting off medical access for thousands of patients. The raid inadvertently spotlighted the cruelty of arresting people who were trying to help the sick and dying, and ended up turning more public opinion in Peron’s favor. Prominent health care organizations in California, including the California Nurses Association, started endorsing Proposition 215.

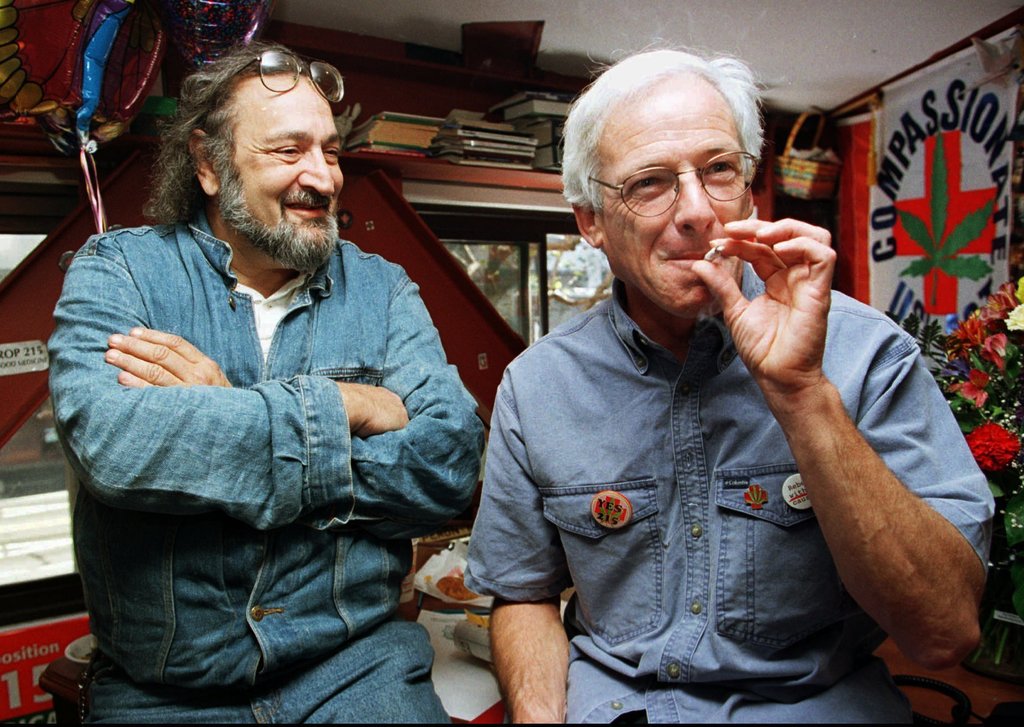

On November 5, 1996, the Compassionate Use Act won in California, with 5,382,915 votes in favor and 4,301,960 opposed (55.6 percent for, 44.4 percent against). In America’s most populous state, citizens could now possess and cultivate marijuana for personal use under state law with a doctor’s recommendation. Standing on Market Street holding his Pomeranian, Peron smiled and lit a joint in front of the TV cameras that surrounded him.

Peron died of cancer on January 27, 2018 at age 72. He stayed active in the cannabis movement until the end of his life. “I came to San Francisco to find love and to change the world,” he said in 2017. “I found love, only to lose him through AIDS. We changed the world.”

Jennifer Boeder is a Chicago-born, Los Angeles transplant who writes about psychedelics, cannabis, music, politics, and culture. Her work has appeared in High Times, DoubleBlind, Cannabis Culture, Civilized, Oxygen, Chicagoist, and Cannabis Now. She attended her first Pride parade high as a kite in 1994.